Remember when we hated bacteria? That was about two or three years ago. Antibacterial soaps were flying off the shelves. We just didn’t like them—any of them.

But things are different now. Communities of microorganisms (the microbiome, or “microbiota” if you prefer) are hot science these days. Gut microbes have been implicated in everything from infectious diseases to obesity, autoimmunity, and depression. There are extended families of symbiotic microbes, which somehow contribute to human health, locked in an eons-long struggle with other organisms that could do us harm.

But humans aren’t the only ones who benefit from a sound microbiome. Beneficial bacteria and fungi are a new frontier in farming—animal husbandry meets genomics, informatics, and microbiology. It’s another emerging way to boost yield and feed a hungry world.

One of the players in this new frontier is Ascus Biosciences, a Sorrento Mesa biotech focused on developing microbe-based nutritional supplements to help livestock thrive.

“We basically make bags that are stuffed with microbes that we sell to livestock producers,” says cofounder and CEO Michael Seely.

Fascinated by Microbiology

Ascus started in an airplane hangar in the Mojave Desert, but migrated south due to the economics. “The Bay Area is a difficult place to start a company that needs a lot of space,” Seely says. He has family in Vermont dairy country, and he’s spent a lot of time thinking about livestock and how they’re grown. Most efforts to improve yields have centered on chemistry, such as antibiotics and hormones, or breeding (mating animals with the best traits). The microbiology route is relatively new.

“There have not been a lot of changes in the technologies being delivered to livestock producers to help them improve farming production, economics, and general animal health and nutrition,” Seely says.

Chief Science Officer Mallory Embree, fellow cofounder and PhD in bioengineering from UC San Diego, has an inherent fascination with microbiology. She used to grow microbes in her bathroom for fun.

“She had wacky ideas to use these different tools that were just starting to become available to do the analysis, but she didn’t have the money,” Seely says.

Their complementary interests seemed like a good fit, and in 2015 they set up Ascus in the Mojave, not far from where Embree’s rocket scientist husband was working. (Seely jokes that they’re going to have really smart kids.)

More Food

Ascus has a simple mission: find the right microbes to improve farming economics. They start with a problem they want to solve, like giving chickens better nutrition to make them more disease resistant.

“We’re building a product that helps organisms withstand some of the environmental pathogens that can make their way into the flock,” Seely says.

The key word is “building.” The Ascus team—microbiologists, genomicists, bioinformaticians, and others—is taking a rigorous scientific approach to finding microbes that support animal nutrition.

Their dairy cow product contains two types of bacteria and one fungus. These microbes are normally found in the rumen, the first of the cow’s four stomachs, where food is bathed in a microbial stew to begin breaking it down. Ascus’s goal is to improve fiber digestibility.

“Animal husbandry meets genomics, informatics, and microbiology.”

“In the rumen, the organisms are helping degrade the animal feed more effectively so that certain protein sources are more available,” Seely says. “You get better digestibility and improved feed efficiency.”

He points out that Ascus produces nutritional products, not therapeutic ones. However, one of the byproducts of better nutrition is the potential for better health, improved pH balance in the rumen and, of course, better milk production. The bottom line is making production more efficient so there’s more food.

Finding the Right Microbes

Ascus isn’t the only company selling microorganisms to farmers, but they’re upping the ante on the science. It turns out that feeding animals random bacteria isn’t the best approach.

“If you look at existing microbial products for livestock—probiotics—people are selling organisms that don’t do anything,” Seely says. “They’re selling a bunch of yogurt microbes because they don’t have the tools to do deep discovery research and development. These aren’t purpose-built products.”

But in the hunt for effective microorganisms, there’s no low-hanging fruit. First, the Ascus research team studies animals, thousands of them, looking at the microbial communities that inhabit their guts and trying to isolate the ones that could do some good.

“Is there a composition of microbes that’s ubiquitous across main-production-line birds that’s native to all of them and could help them resist different degrees of environmental pathogens and improve gut health?” Seely asks. “If you have a healthy gut, you have a higher-producing bird. You go out in the world and mine nature to find that.”

2.1 million

farms in the U.S.

(Source: USDA, 2014)

23.7 billion pounds

of beef produced in the U.S. in 2015

36.9 billion pounds

of chicken produced in the U.S. in 2010

$151 billion:

total value of US agricultural exports

Identifying and isolating useful bugs is painstaking work. Next-generation sequencing is combined with advanced informatics, protein analysis, and flow cytometry (high-throughput cell detection) to identify useful organisms. But that’s only the start of the process—and not even the most difficult part.

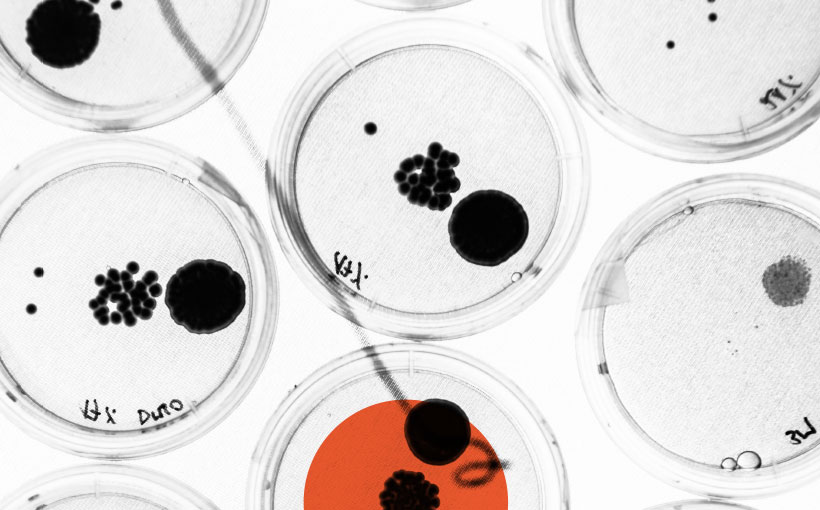

From there, microbiologists must isolate and grow target microbes using petri dishes, which are 19th-century technology. Some bugs are difficult, or impossible, to culture. Plus, the original samples are complex, containing thousands of microbes, and the fast-growing strains can out-compete their slower cousins.

“The ones we’re interested in aren’t the most abundant,” Seely notes.

Once a specific strain is isolated, the team needs to figure out what it is and what it does. Sometimes it’s not the microbe they’re after but the molecules the microbe produces: proteins, enzymes, or metabolites. But even after all that work, there’s no guarantee it’s going to be a

viable product.

“We have to choose microbes that we can grow, scale up, and ferment cost effectively,” Seely says.

This is no simple task. Ascus’s bags of

microbes have to come in at a reasonable price to make the economics work. Farmers don’t have the cash to buy a feed supplement priced like a pharmaceutical.

Focused Mission

Seely notes that some in agriculture, particularly the poultry side, are eager to reduce their antibiotic use, but that’s not what Ascus is about.

“We’re not interested in changing anything,” says Seely. “We’re interested in building products that create value.”

Ever since they moved to San Diego, the company has gradually expanded. They have around 20 people now, many of them young researchers excited by the groundbreaking work.

“Being able to incorporate these genomic and computational tools for people to interpret microbiology much more comprehensively, that’s a neat thing for creative scientists,” Seely says. “We get around a thousand résumés for a basic research associate job. We screen for people who don’t have a preference for formalized processes. We believe that obstructs the creative process.”

The company is working on expanding their offerings to the swine and aquaculture markets. Fish farming is a tough area, and it may take them a while to develop the right organisms. But the people at Ascus seem to enjoy the challenge and, when in doubt, Seely says they always circle back to the mission:

“Our goal is to make products that deliver value and do so in a way that’s natural.”

What’s up with the microbiome?

There are around 10 trillion microbes in our bodies, outnumbering human cells 10 to 1. While that’s an interesting factoid for dinner parties, what does it actually mean?

What They Can Do

We have microbes all over our bodies, but the most significant concentration is in our gastrointestinal tract. That payoff is pretty amazing. If microbes only helped digest food, that would be more than enough to pay the rent. However, the list of microbial ROI is long and getting longer. The microbiome is our first line of defense against pathogens, often preventing them from getting a toehold in the bloodstream. Poop transplants, which we chuckle at like third graders, introduce microbial reinforcements to fight antibiotic-resistant C. difficile.

Studies have linked microbial dysfunction to Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes, and many other conditions. One recent paper even investigated how marital stress might alter the gut microbiome.

Balance

One of the key attributes of a healthy ecosystem is balance. Scientists aren’t entirely sure what a well-balanced microbial landscape looks like, but they’re getting there.

Some studies have linked microbial imbalances to inflammatory bowel disease, obesity, depression, and allergies. Prescribing antibiotics to infants could throw their gut flora out of balance, which may prove to be one explanation behind the spike in food allergies in the past 20 years.

Gut-Brain Access

It’s one of the hottest research topics in this field. Some hypothesize that an imbalance in gut microbes may contribute to schizophrenia, OCD, ADD, autism, and other neurological conditions. Expect major revelations in the next few years.

Tags: Bacteria, Biotech, Farming, Genomics, Microbiology, Next Big Thing