Up on Torrey Pines Mesa, thousands of scientists at UC San Diego, The Scripps Research Institute, and other facilities spend their careers trying to understand the biology behind disease. Sometimes there’s a eureka moment, and a lab discovers how an aberrant protein throws a wrench in the cellular machinery. A paper is published, newspapers and websites tout the achievement, taxpayers and philanthropists see return on investment.

But what then? As important as these lab successes are, they are miles away from actual treatments. To get there, entrepreneurial scientists need time, patience, and money. For anyone trying to commercialize a basic scientific discovery, this last element is almost always a sticking point.

“Life sciences is a unique industry,” says Jay Lichter, managing director at Avalon Ventures. “It takes 15 years to develop a product. It costs, on a fully amortized basis, around two billion dollars. It’s not like a tech company, where a CEO can come in and in 18 or 24 months they’re generating 10, 20 million dollars.”

To complicate matters, most prospective therapies fail in clinical trials, adding another layer of risk. Yet the promise of better treatments, and return on investment, keeps San Diego’s biotech VCs coming back. They’re a seasoned bunch, and they know where the potholes lie. The trick is avoiding them.

The Right Fit

VCs, and their close cousins, angel investors, develop loose equations to evaluate potential investments, but the science is always one of the key variables. What can it accomplish? How will it help people?

“I’m not interested in me-too approaches,” says Ivor Royston, managing partner at Forward Ventures and co-founder of Hybritech, San Diego’s first biotech. “It’s always about something that’s innovative, new, and disruptive. The best opportunities are great science, unmet medical need, and freedom to operate; nobody else has patents to block you.”

But good science is just the start. Business is a human enterprise, and the science is nothing without a good team to back it up.

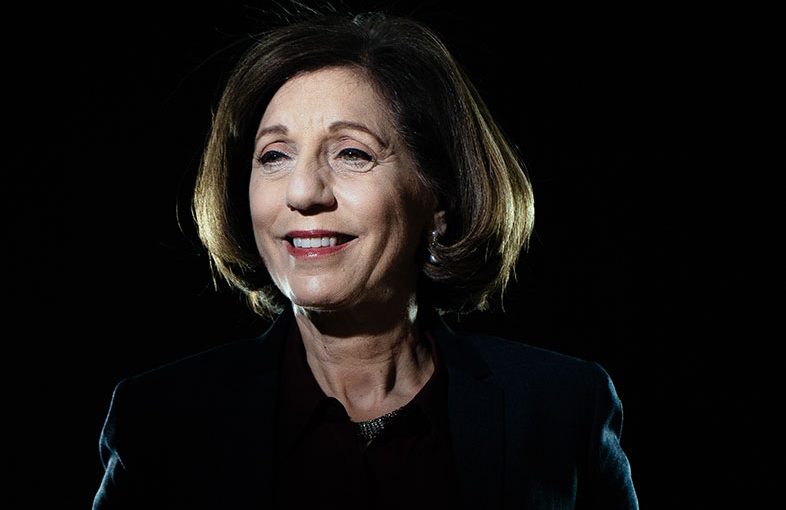

Dan Bradbury, Managing Member, BioBrit

“It doesn’t matter how great the technology is; it doesn’t matter how great the unmet medical need,” says Dan Bradbury, managing member at BioBrit. “At the end of the day, the team that will be executing the business plan is the most important thing.”

That mantra—find the right people—is repeated often, and can be particularly important for nonscientists diving into biotech. Barbara Bry and Neil Senturia, who founded Blackbird Ventures, are primarily tech investors who have taken a chance on Abreos Biosciences based largely on their trust in its founder, Bradley Messmer.

“If we don’t have domain expertise, but recognize it in other people, that’s an investable opportunity,” says Senturia. “Brad Messmer knows PK dosing [how the body reacts to a drug] and all the science and all the studies. He knows it ice cold. I like that.”

But even with ample due diligence, the life sciences are incredibly risky and investors must take their lumps. As many as 95 percent of drugs fail in clinical trials. And even after FDA approval, companies must often lobby Medicare and private insurers to get their products paid for. Without reimbursement, startups can be dead in the water, as Bradbury recently learned with a medical device company.

“I didn’t fully understand the reimbursement challenges,” he says. “It looked like a really good idea, but the company is going to have to finance itself for a couple of years before it sees Medicare reimbursement. That’s a long time for a small company.”

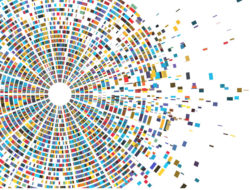

The High Cost of Drug Development

In 2014, the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development found that drug development—soup to nuts—costs more than $2.5 billion. While this figure is not without controversy, it does provide a framework to discuss the issue.

The costs included around $1.4 billion in out-of-pocket expenses, along with $1.1 billion in time costs, or the money investors don’t receive while the drug is being developed. The Tufts study also factored the high failure rate into the cost of success. Of the 1,442 compounds studied, more than 80 percent failed in clinical trials.

The cost of developing a drug:

$540M – Identifying a potential drug

$290M – preclinical studies

$343M – phase 1 clinical trials

$666M – phase 2 clinical trials

$691M – phase 3 clinical trials

$13M – approval

Total: $2.5B

The VC as Caring Nurturer

Choosing the right team is important for another reason. VCs and entrepreneurs become partners and, like any partnership, must share commitment, values, and vision. The relationship requires constant work.

“If you’re going to be effective, you have to be deeply engaged,” says Senturia. “It’s like getting married. If you don’t like being around them, that makes no sense at all.”

Jay Lichter, PhD, Managing Director, Avalon Ventures

Commitment is particularly important when financing young entrepreneurs, who may have strong scientific chops but lack business seasoning.

“When I’m with a new CEO, I tend to carve out a lot of time for them,” says Lichter. “With first-time CEOs, there’s a half dozen mistakes they’re going to make.”

Lichter notes that young CEOs often underestimate how long a process will take or how much it will cost and have trouble delegating in support areas, like accounting and IT. He is particularly concerned that this go-it-alone mentality can burn out an entrepreneur years before a product gets close to market.

“You can do a lot, I tell them, but you can’t do everything,” says Lichter. “Make sure everything gets done and take care of yourself.”

Sometimes the marriage is about putting together complementary skills to complete a team. It’s critically important for entrepreneurs to know what they don’t know.

“Brad [Messmer] has a good awareness of what he understands and what he needs help with,” says Bry. “He turns to Neil regularly for advice on financing, strategy, and how to develop strategic partnerships.”

VCs manage these relationships in many ways: by setting up incubator facilities where entrepreneurs can experiment, by sitting on multiple boards, and sometimes by leading a company. Bradbury spends a lot of time coaching CEOs.

“I’m like the Bat-phone, basically. I work with them when they have an issue.”

Investment Jargon We All Should Know

Angel Investor: A person who invests in an early startup in return for a stake in the company. Sometimes the individual investor will use capital from friends and family.

Funding Round: VCs fund companies in rounds. The initial investment is the seed round. Subsequent rounds are labeled

A, B, C, etc.

Incubator: An organization that helps entrepreneurs develop their early-stage companies.

Proof of Concept: The company needs to show investors their technology is feasible.

Stage: Companies have life cycles, starting with seed, then early, mid, and late stage. VCs often focus on seed and early-stage companies.

Venture Capitalist (VC): A firm that invests in small, often risky startup companies in return for a piece of the company.

Sometimes It’s Personal

VCs and angels invest money and time, but in many cases, it’s more than just getting a nice return—it’s personal.

Ivor Royston is an oncologist by training and didn’t even know what a VC was until he started Hybritech in 1978. Royston was on a mission to improve cancer treatments. Later, he helped found Idec Pharmaceuticals, another San Diego success story. The company developed Rituxan, a highly effective blood cancer therapy. Investing has helped him have an even greater impact.

“I’m living vicariously through other scientists,” says Royston. “I realized I wasn’t going to make all the inventions.”

Jay Lichter is particularly proud of Otonomy, a company that develops treatments for middle and inner ear disorders. After experiencing debilitating vertigo, Lichter was diagnosed with Ménière’s disease, which affects fluid in the inner ear. His treatment options were either steroids or surgery, neither of which had much appeal.

Instead, he worked with an ear, nose, and throat specialist to develop a slow-release treatment, which ultimately led to Otonomy.

“I’m very proud of that company, because it’s personal to me,” says Lichter. “It’s what I love to do: find an unmet need, an overlooked opportunity, a white space and, despite people saying I’m nuts, go for it.”

Some companies succeed and some fail—it’s just part of the business. Investors hope winners outpace losers, but sometimes there is comfort in failure.

“If you look at our list of failed companies, there are failures that make you happy because you tested a hypothesis and found out it didn’t work,” says Jim Blair, a partner at Domain Associates. “Whether it succeeds or fails, you’ve done a good thing. If you don’t test the hypothesis, you haven’t put your money where it can do the most good.”

Neil Senturia, Blackbird Ventures

Scanning the Horizon

Investors are always looking for that hidden gem, and with so much innovation in San Diego, there are lots of options. Bradbury is especially interested in precision medicine—using genomic sequencing to select cancer treatments, for example.

“The idea that you target a medicine specifically to the molecular disturbance as opposed to treating symptoms—and it’s specific to that patient. I think that’s incredibly exciting.”

But improving health can mean more than developing a novel therapy or precision diagnostic. Access to care has become a major issue. The Affordable Care Act added millions of new patients without necessarily fortifying the medical infrastructure. Providers will have to find creative ways to become more efficient.

“We see a big part of that solution as diagnostics, which account for only about 2 percent of health care spending,” says Blair. “They provide 60 to 70 percent of the data physicians need to treat patients. If we’re going to increase productivity, we need to collect information in a more timely way.”

Blair and others think wearables—more sophisticated versions of Fitbits and Apple Watches—will help fill that gap.

Still, scanning the horizon also means looking for trouble. Many investors are concerned that high drug prices are becoming a hot topic.

VCs are paying close attention to this debate, as it could dramatically alter their business model and even divert them to less regulated industries. “There has to be a sufficiently big win for the winners or nobody is going to take the risk and eat the losers,” says Lichter.

Jim Blair, PhD, Partner, Domain Associates

The Mother Lode

San Diego doesn’t have a large biotech investor community, but the ones who are here really like what they see.

“There’s no environment like San Diego in terms of life science collaboration,” says Bradbury. “One of the hallmarks of the industry here is the way people connect and enable each other.”

This, in part, has created a culture of serial entrepreneurialism. It goes all the way back to Hybritech, which was sold to Eli Lilly in 1986 but continues to pollinate the life sciences community. Former Hybritech stars have founded dozens of companies and inspired new leaders to go out on their own—rinse and repeat.

“You have an executive nucleus that came out of those roots, and not only did it again after they came out of Hybritech, but did it again and again and again,” says Blair. “We see this space as the mother lode of entrepreneurial activity.”

The San Diego Conundrum

Unlike life science hubs in San Francisco and Boston, San Diego doesn’t have a large biotech company to call its own. While Illumina dominates the genomic sequencing world, they don’t make any therapies.

Over the years, San Diego’s successful biotechs have been sold or merged into other companies. Hybritech was sold to Eli Lilly and Agouron to Warner-Lambert. Idec merged with Biogen and moved to Boston. Receptos was recently purchased by Celgene.

The VCs we chatted with gave a number of reasons for this ongoing churn, such as the city’s entrepreneurial nature—fully developed companies are boring—and the lack of seasoned professionals to commercialize products. However, they don’t see it as a bug, but as a feature.

“Big pharma recognizes they can’t develop new drugs as well as a biotech can, so they come into town and buy up our companies,” says Barbara Bry. “In the old days they transferred the technology and closed it down, but that’s changing. Arden under AstraZeneca has grown from around 120 to 170 employees. I think this is a new model, where big pharma buys a San Diego company and grows its presence in San Diego.”

And for VCs, this ongoing interest in San Diego’s biotech startups creates a nice environment.

“We’re in San Diego because it’s not San Francisco and it’s not Boston,” says Jim Blair. “Our choice of San Diego is deliberate.”